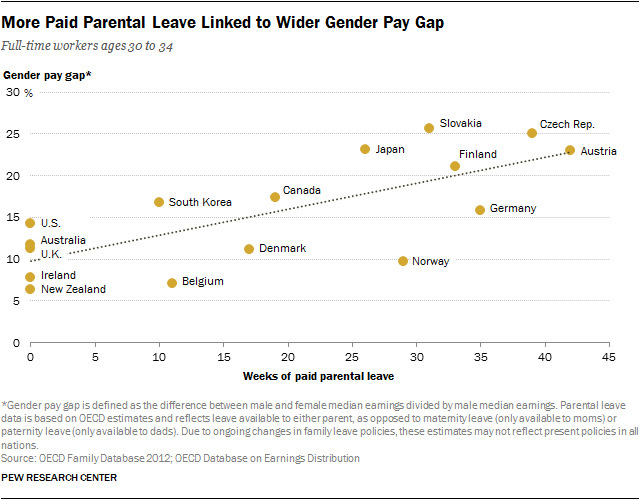

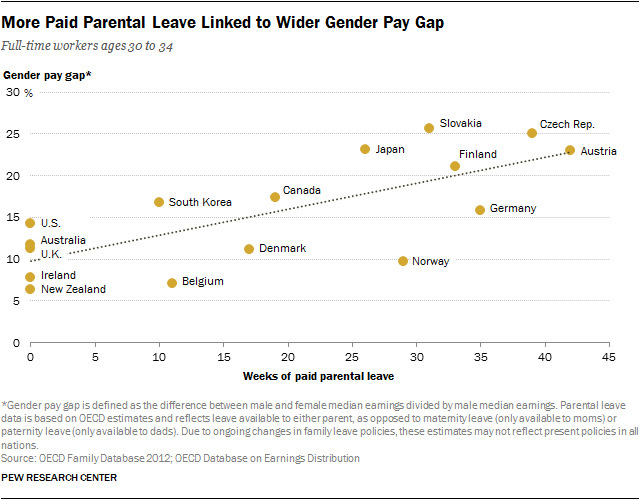

Look at this graph, look at it closely. What does it say? Where government programs create parental leaves program paid for by employers, the wage gap between women and men in their early thirties is greater and the longer the duration of these payments, the greater the gap grows. How does this hold econometrically? Relatively well.

Longer maternity leaves in Germany have lasting effects on the long-term earnings of women. However, the expansion of maternity leave programs did not have any lasting negative effects on the long-term supply of labour of female. In short, women were incited by government policy to stay longer off the market which had a detrimental effect on long-term wages. This seems to hold across Europe as a whole (here).

But more simply, it creates inequality. That government program incentivizes families to reduce the time spent at work at the expense of future earnings. Whilst as a society, we might value the presence of mothers at home (and hence value maternity leave programs) but we have to understand that this comes at a cost : higher inequality between male and female. This is the case because longer periods spent off the market have a large effect on the wage gap. As the OECD recently explained in a 2013 paper :

However, if employees take up very long leave entitlements, they may become detached from the labour market as their skills depreciate. They might also have trouble getting the same job back.1 Moreover, the extent to which leave mandates produce positive outcomes for women also depends on how employers respond. Some may be reluctant to hire women, whom they perceive as more likely to take leave, if similarly qualified male workers are available. They may also seek to keep women in jobs where time off has a limited impact on the production process or where it is relatively easy to replace them. Plainly, however, the different perspectives on the labour market outcomes of paid leave mandates make it difficult to draw conclusions with any certainty as to the overall effect.

This conclusion would hold even if the policies were “equalized” to incite men to stay at home in equal proportions to women because the wage gap between men would grow (logically, unless men across the income distribution chose to stay at home in proportions representative of their income – something I find unlikely) . If governments want to have policies that will increase the incentives to have kids – programs like parental leave – they must understand that the counter-effect is that they end up generating inequalities that they will condemn. You may want that policy – I don’t think it’s a terrible policy (in principle) – but you can’t complain about the results you knew you were going to get.

When I scream out my lungs that governments are much better at creating inequalities (that they will then condemn) than they are at reducing them, this is a good example.

H/T : Francis Pouliot