In recent times, Jeffrey Williamson and Peter Lindert have been attempting to assert that American living standards were much higher than in Britain in the colonial. An important part of their claim centers on the differential of purchasing power parity. This makes America looks richer on the eve of the American revolution. I don’t dispute that part.

However, I do dispute that it was something exceptional within the thirteen colonies since I think that the colony of New France, a small settlement of roughly 60,000 individuals in 1760, had a similar advantage over its mother country of France and likely over Britain. I can’t be sure about how it stood relative to America (I am still playing with my creation of output and wage estimates), but its level of living standards should not have diverged too much from those observed in America.

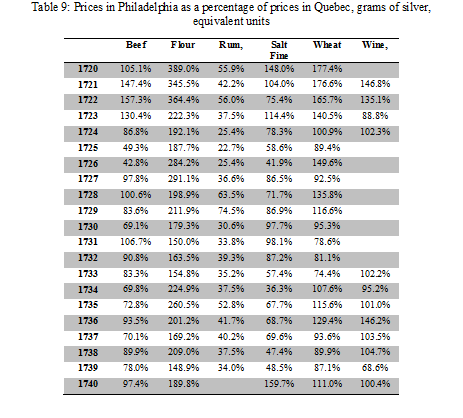

Why do I say that? Well here is a table from my thesis which compares prices in France to prices in Quebec (prices in Quebec divided by prices in France). As you can see, prices in French America – except for import prices – are considerably lower than those in France. In my modest opinion, this means that a parrallel can be drawn between Lindert and Williamson’s focus on British/American purchasing power and French/Canadian purchasing power.

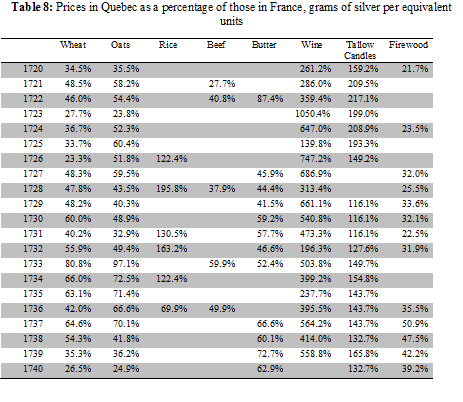

So what about prices in Quebec to those in the Colony? Here, I am more prudent since converting currency units is extremely delicate. However, using the Hoffman rates for the grams of silver per livre permits me to draw the following image of the differences in prices between Quebec and Philadelphia. For flour, wheat and wine, the inhabitants of Quebec had to pay less than the inhabitants of Philadelphia while the latter paid less for rum, beef and salt.

So what about prices in Quebec to those in the Colony? Here, I am more prudent since converting currency units is extremely delicate. However, using the Hoffman rates for the grams of silver per livre permits me to draw the following image of the differences in prices between Quebec and Philadelphia. For flour, wheat and wine, the inhabitants of Quebec had to pay less than the inhabitants of Philadelphia while the latter paid less for rum, beef and salt.

From this, its hard to assert something about the relative purchasing power of the two colonies. However, I think it makes the American colonies seem less exceptional in economic history. This makes me think also that the real question is not whether or not colonial economies overtook “old world” economies, rather the question is why did that one (the US) actually had faster growth for most of the 19th century and Canada’s growth only took up in the late 19th century and early 20th century?

NOTE: This is all still formative thinking. However, the tables presented for prices are pretty solid.